Our Solar System in True Color Is Really Something Else

Venus is white. So is the sun. They’re beautiful anyway.

/media/cinemagraph/2022/02/02/venus.mp4)

Picture Venus. You know, the second planet from the sun, where the clouds are shot through with sulfuric acid and the surface is hot enough to melt lead.

What color is it?

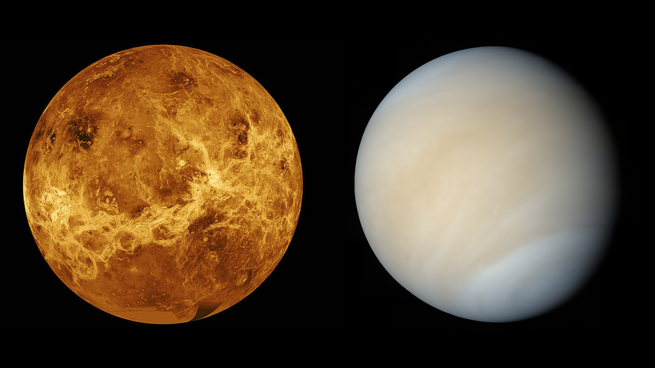

For the longest time, I thought of Venus as caramel-colored, swirled with golds, yellows, and browns—warm colors that matched the planet’s reputation for being a scorching world covered in volcanoes. And then I saw a picture of Venus that James O’Donoghue, a planetary astronomer, shared online recently. It was not any toasty shade, not even close. It was milky-white and featureless. A big old space pearl. “This is what it looks like to a human being flying by,” O’Donoghue wrote in his post.

Whaaat? That couldn’t be right. I went to my bookshelf and pulled out some space books, flipping to their pages on Venus. In National Geographic’s Space Atlas, Second Edition: amber. In The Smithsonian History of Space Exploration: butterscotch. In a thick magazine called the Book of the Solar System: gold. My editor sent me pictures of the illustrations from her toddler’s books on the solar system, and they showed more of the same. It seemed as if we had all been bamboozled, hoodwinked, led astray. I had seen pictures of Venus in muted shades before—I’d used one in a story about the planet’s atmosphere—but this other nondescript, alabaster world seemed wrong. It didn’t resemble a planet frequently described as “hellish,” where the surface conditions have crumpled any spacecraft that made it through the poison clouds and dared to land.

I was so stunned that I reached out to one of my best Venus sources and demanded, “Why didn’t you tell me?” Suddenly I had questions about the whole solar system, and so did the rest of The Atlantic’s Science desk. As one of my colleagues asked, when I told him about the true nature of Venus, “Is Jupiter’s Great Red Spot even red?”

It turns out that almost nothing in space is quite as vibrant as you think it is. Venus is only the beginning.

The most widespread image of Venus—as an ochre, almost molten world—isn’t a real picture, at least not in the typical way we think of pictures; it was made using radio waves. In the early ’90s, a NASA spacecraft equipped with radar technology settled into orbit around Venus. Every time the probe, named Magellan, came close to the planet, it collected strips of data from all over Venus and sent them back to Earth. Eventually, the mission amassed enough strips to produce the first-ever radar map of the Venusian surface. We can’t see radio waves, so astronomers translated them into colors that we can. They could have picked any color palette, O’Donoghue told me. He imagines they went with this particular set “because it befit the harsh, burnt landscape of Venus.”

The Magellan shot was a significant upgrade over existing images of Venus’s exterior, captured by a space probe in the ’70s, which showed creamy-white cloud tops and not much else. Suddenly, mountains and craters were visible. The scientists who study Venus loved the orangey version, even though it was an interpretation, Martha Gilmore, a planetary geologist at Wesleyan University who studies the Venusian surface, told me. “That color has permeated the Venus community since then,” she said. “It’s in our logos.”

Sorry to our human eyeballs, but apparently Venus just looks better in wavelengths we can’t visually process. Because its sulfuric-acid clouds are so bright and reflective, “the planet itself looks pretty bland from space in the visible spectrum,” Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University who studies Venus, told me. That image of a muted Venus I’d used before was the planet in ultraviolet. Where the radar image helped tease out Venus’s surface features, ultraviolet brought out swirly structures in its fast-moving clouds.

Like Venus’s classic portrait, most of the pictures of planets and other astronomical objects that you’ve seen, in textbooks or on NASA websites, are not natural-color views. They’re rendered in different wavelengths, stitched together from raw data. Or the colors that really would be visible to the naked eye are adjusted in some way, heightened in order to show a more textured view of these worlds, to make their features pop, whether mountains or storms. “We don’t turn up our noses at artificial color,” Candy Hansen, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute who leads the imaging team on a Jupiter mission, once told me. “We love artificial color.”

So although in most pictures the Great Red Spot looks like a glob of marinara, in natural color the giant storm is more of a dusty rose. Seen from space, Mars is more brown than red. Saturn isn’t really so yellow; it’s actually the kind of nice neutral you’d paint a living room. Uranus is more gray than it is teal, and Neptune is a lovely azure, but not that blue. Pluto’s heart-shaped glacier doesn’t stand out as much in true color.

And the sun? “The sun is nearly always depicted as yellow-orange when in space, even though it’s actually white in space,” O’Donoghue said. “It’s actually a lot of extra work to pull off a realistic sun in a space graphic, because a white ball looks really odd.” Once again, whaaat?

So if Venus is a ping-pong ball on the outside, what color is it below the clouds? Scientists know that the surface is made of rock that resembles basalt found on Earth, which is dark gray, Byrne said. But chemical reactions between the rock and the atmosphere could turn the surface reddish. The Soviet missions that landed on the Venusian surface in the ’70s and ’80s took color photographs, revealing a yellowy landscape, before they succumbed to the harsh environment. But the true color was difficult to determine because Venus’s atmosphere filters out blue light.

Astronomers will get a fresh look when a new NASA mission, designed to fly right through Venus’s atmosphere and toward the surface, arrives in the early 2030s. Those pictures will be in near-infrared wavelengths, but astronomers will once again translate them into more distinct colors for the public to marvel at. Those images are bound to be stunning in their own way, but now that I’m past the shock of it, I can understand the appeal of Venus the way we’d see it ourselves, as the pearl of the solar system. “It’s a beautiful planet,” Byrne said. “Even if there’s, like, a bunch of different ways to die there.”