In one Ukrainian Telegram group for those who have lost loved ones in Mariupol, its more than 26,000 members have one objective: ensuring the thousands who died during the Russian assault on the port city are given a proper burial, and in many cases finding their remains in the first place.

The number of bodies in Mariupol is overwhelming. Petro Andryushchenko, an adviser to the Ukrainian mayor, estimated that 22,000 died in the two months of fighting. However, a person among several coordinating burials in the city who spoke on condition of anonymity said they believed the total was closer to 50,000.

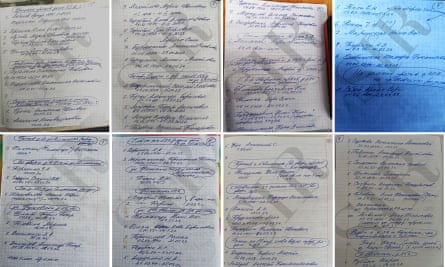

Some of those in the messenger app group know where their loved ones are buried and are navigating the chaotic burial process under the new authorities. Others spend their days scrolling through social media groups for news, and fear they may never find them, while fellow members post photos and videos of grave markers, as well as photos of handwritten lists of the dead, occasionally with burial locations, written by unknown authors.

With the temperatures rising as summer approaches, the odour of dead bodies wafts down certain streets, people who have been in the city told the Guardian.

There are bodies are still trapped under rubble or in flats or buried in shallow makeshift or mass graves – a number of which appear to have been poorly marked or even unmarked. Others were left in the street and rotted, and some may have disintegrated if they were hit directly or burned in a fire.

“I joined the group to let people know that my father had been killed and, I don’t know, to share my grief,” said Mariana. She said she lost contact with her parents who lived in another part of Mariupol when the phone signal was cut at the beginning of March. The shelling had made it too dangerous to reach them before she left with her children two weeks later. Her father was killed putting out a fire and her mother buried him with her own hands next to their apartment building, before leaving herself, said Mariana, who plans to make the journey back to Mariupol next month to rebury her father properly.

Deaths such as her fathers are among a spreadsheet of more than 1,200 people created by members of the Telegram group, which includes information about how they died and often where they are buried.

The cause of death section listed on the spreadsheet evokes the horrors the encircled civilian population underwent: death from hunger, lack of medicine and lack of medical treatment, heart attack, Covid and stroke. Died when their apartment was bombed, bombed while trying to get water, died while putting out a fire, froze to death, shot dead, and died from shrapnel wounds.

The battle for Mariupol was fought over a densely populated city of an estimated 400,000 people. The Ukrainian army sent shells and missiles out and the Russian army’s response crashed back into residential areas, say residents. They say they still want to know why they were not evacuated and why they became “hostages” in a war that their mayor – who fled on 27 February – said would not happen.

As the barrage of bombs made movement almost impossible, the courtyards between apartment blocks started to fill with makeshift graves dug by residents amid the shelling. Some of the grave markers are handmade, others were given to people by the emergency services who took them from a local funeral home.

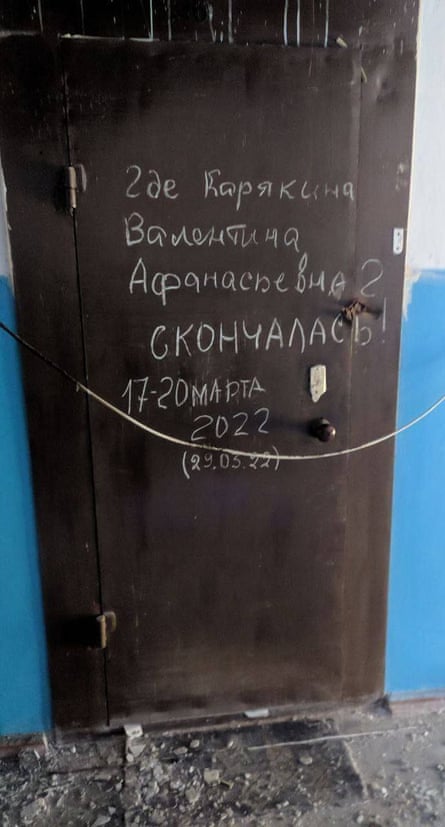

But sometimes even makeshift graves were not possible. A picture in the Telegram group shows a dead person’s name and date of death scrawled across an apartment door with paint, presumably written by a neighbour who wanted to leave a record for whoever would later retrieve the body.

Yulia, who left Mariupol for Russia as an adult many years ago, said she found out through her former classmates on Telegram that her father had died in his apartment in late March. Her father’s neighbour told her he had wrapped him in a blanket, taken him outside in a wheelbarrow and left him next to their building.

“[The neighbour] didn’t bury him because it wasn’t safe. Perhaps some [emergency] services took the body later because it began to warm up and hungry dogs were running around everywhere. I even watched a video of dogs eating corpses, it’s just awful. I’m afraid to even think about it,” said Yulia.

Yulia wrote to the new city agency that has been set up to identify bodies and issue death certificates. They replied that her father was not on their list of identified bodies and asked her to come to Mariupol to give a DNA sample.

“From their letter, it seems his body will never be identified. I think maybe the neighbour failed to leave any documents with his body,” said Yulia, who says she will return to Mariupol as soon as she can to look for her father’s body.

The new authorities say the burial and identification process is in hand and that each body will be buried separately in a humane manner. But Telegram posts by people burying their dead show the process appears to be rife with problems.

Since Russia declared victory in April, Mariupol has come under the control of the self-proclaimed republic in Donetsk, a Russian proxy authority created to oversee Ukraine’s occupied eastern Donetsk region in 2014.

Videos shot by the Donetsk authority’s TV channels show emergency workers digging up bodies from the makeshift graves and retrieving bodies from the rubble. They say they are in the process of making their way around the city with the aim of burying or reburying all the bodies. The authorities have publicly invited relatives to exhume bodies themselves, but this does not seem to involve supervision.

Bodies are taken to the only Mariupol morgue still functioning, the Metro morgue, to be examined and registered, if the state of the body allows or if ID is found on the body.

Photos of the Metro morgue taken by a Mariupol journalist, Vyacheslav Tverdokhleb, show piles of bodies in the courtyard next to people with face masks. On Telegram, one person who had been there warned others of the strong smell – which, they write, “starts on your approach”.

“It’s like this: you’re queueing to get your death certificate in the yard and there are just piles of bodies next to you,” Daria said, who left Mariupol at the end of March but returned for two weeks in May to bury her close friend on behalf of his relatives.

If the bodies go unclaimed or unidentified for two weeks, the authorities will bury them in graves marked with numbers, according to Telegram posts written by a representative of Ritual, the only funeral home still operating in the city.

As hundreds of thousands have left the city and cannot easily return, many are trying to employ the services of Ritual from afar.

Ritual, a formerly private turned state company of the breakaway Donetsk authority, offers a paid service to dig up or retrieve a body if its whereabouts are known and bury it. This way, as one of Ritual’s representatives wrote in posts on their Telegram channel, relatives can avoid the stench or worse yet, their loved one’s body being lost in the bureaucratic chaos of Metro morgue or buried in a mass grave.

Satellite images from the company Maxar and a CNN report, both taken after Russia took control of the area, show that Russian forces have dug mass graves. The CNN report, and another video posted on Telegram by Ritual on 9 May, from cemeteries outside Mariupol, show that the mass graves are numbered, and probably relate to a database the authorities are said to be keeping.

Daria and one other person the Guardian spoke to, as well as posts on Telegram by those who had been through the process, say that the Donetsk authorities have a database with photos of the bodies and other information left on the body.

But not all the bodies that should appear on the database are coming up. Olesya’s husband died and her child was seriously wounded when a rocket hit their apartment in March. Olesya decided her only option was to take her child to a doctor and she left her husband face-down near the entrance of their building. Now she cannot find his body and does not know if he has been buried. But, she says, his documents were next to him in the pocket of his jacket.

“I think most likely he will be a missing person now,” said Olesya, who said that all the neighbours fled at the same time because their apartment block was burning, along with five other blocks around them.

The Donetsk authorities say relatives can give DNA samples for identification, which in theory indicates that they are collecting samples from the bodies. But a person coordinating burials said they had not heard of such a practice or database.

If DNA samples are not collected, thousands of bodies may never be identified and the scale and truth of what happened in Mariupol will never be known. Ukraine’s authorities accuse Russia of using the mass graves to cover up their crimes.

“They should let the Red Cross in to oversee the process, collect DNA from the bodies and create a database which should be handed over to Ukraine,” said Serhiy Taruta, a Mariupol native, Ukrainian MP and oligarch whose businesses used to employ thousands in the city.

*Some names have been changed to protect people’s identities