The hidden images found in masterpieces

Oxia Palus

Oxia PalusFrom ancient scrolls to Dutch Golden Age paintings, technologies are discovering new clues about the world's greatest art works.

The history of art is filled with lost masterpieces, paintings and artefacts that have been destroyed, altered or even painted over by the artist and discovered centuries later. After the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, whole libraries of ancient scrolls were turned to charcoal and are now too fragile to be unrolled. One of Rembrandt's greatest masterpieces, The Night Watch (1642), had panels chopped off each side in order to fit through the door of Amsterdam's Town Hall, where it was installed in 1715. We have long accepted that works such as these might never be known to us, but in recent years this assumption has been upended.

More like this:

Much as AI, or machine learning, has been woven into the rest of our daily lives, it's now taking a shot at resurrecting precious cultural artefacts once lost to the passage of time. For most of history it was not unusual for an artist to reuse canvases, which could be hard to come by. One project that has grabbed headlines in recent years, led by two science PhD students George Cann and Anthony Bourached, working under the name Oxia Palus, has attempted to resurrect some of the works that are now known to us only through X-rays. Their AI-rendered images (the first was made public in 2019) aim to give back an idea of the lost painting's original colour and texture.

In one example, Modigliani's Portrait of a Girl (c 1917), they have brought into the light a woman that the artist once attempted to conceal. She is believed to be the English writer Beatrice Hastings, an ex-lover with whom he had a notoriously stormy relationship. He may well have tried to erase her memory once their affair ended in 1916 (although several portraits of her do survive).

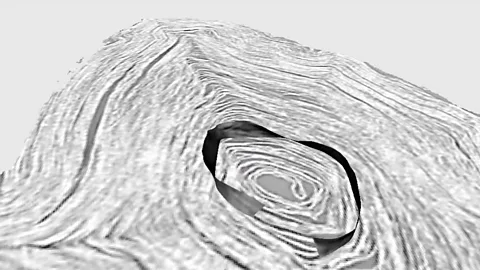

The two researchers have converted their reconstructions into 3D prints that are being sold under the name NeoMasters. "I think these have interested people because they like things that are new," Bourached tells BBC Culture. "It would be amazing to see all these masterpieces, which exist but that you'll never see because nobody is going to get a chisel out and scrape off part of a multi-million-pound painting."

Oxia Palus

Oxia PalusThe pair are wary, however, that news headlines can oversimplify their work. "The story that grabs attention is 'AI reconstructs a painting', as if there's a button that we press and the whole process is done," says Bourached. This can give the impression that scientists are handing over complete authority to machines when, in fact, he says, "there's lots of human input along the way".

The human contribution includes gathering a dataset of works by the artist for the machine to learn their style and cleaning up the X-ray image to remove elements from the surface painting. The resulting X-ray images are "very much our interpretation of what's underneath," Cann tells BBC Culture. The pair describe it as a "sloppy process", just an experiment produced in their spare time with no funding. "One of the points we want to make is that, even with a relatively naive approach, this is what can be done," adds Bourached. "I'm hoping that other people will take this nascent field and do better things with it."

Bringing art and science together

One barrier they came up against was the limited information provided by traditional X-rays, which were first used on paintings in the 19th Century. Conservators also take samples from the canvas to find out more about materials, pigments and possible damage but newer scanning technologies allow them to get all this information without touching the work.

Five years ago, the National Gallery in London acquired new state-of-the-art scanning equipment capable of capturing so much data about a single painting that most cultural organisations are poorly equipped to make much use of it. Some are now initiating cross-sector collaborations with universities that can offer superior computing facilities and broader expertise. As part of a recent partnership with University College London and Imperial College London, called Art Through the ICT Lens, or ARTICT, the National Gallery has been producing much clearer images of Francisco de Goya's Doña Isabel de Porcel (c 1805), a fashionable young woman wearing a black mantilla (scarf). In 1980, a mysterious second portrait of a man in a waistcoat and jacket was discovered underneath. Getting a clearer image of the man has meant combining multiple scans from different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, some of which reveal certain aspects of the painting better than others. At first, this process had to be done manually but thanks to this new research, it has now been handed over to a computer.

Francisco de Goya

Francisco de GoyaThe UCL researchers, led by Dr Miguel Rodrigues, had previously worked on a similar project for the restoration of Van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece (1432). The large-scale work is made up of many panels, some of which are double-sided so that it can be opened and closed. The exterior panels, showing the annunciation and a row of patrons and saints, were visible most of the year, but the altarpiece would be opened to reveal other religious figures and the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb on special feast days. The double-sided panels have produced layered X-rays that are particularly tricky to interpret, a problem for conservators hoping to study different layers of the painting. The algorithm developed by Rodrigues and his team managed to separate them into two distinct images.

Jan van Eyck

Jan van EyckAchieving this with the murky X-rays of the Goya is a bigger challenge, as the researchers did not already have an idea of what the painting underneath should look like. Instead, they mixed up X-rays of other paintings to see if the algorithm could learn to separate them. In this case, the algorithm is known as a "black box", meaning it may produce good results but it is not always clear how. To try and understand this better, the team looked at outputs from different points in the learning process and experimented with how feeding the machine data in different ways might improve the output.

"One of the things that is particularly difficult to work out is what is good and what is better," Catherine Higgitt, Principal Scientific Officer at the National Gallery, tells BBC Culture. "We're separating an image into two hypothetical images, but what is it we're trying to get? Is that something useful to a conservator – interested in damage, cracks and subsurface details – or something that looks as close to the image at the surface as possible?"

Questions like these demonstrate the strength in collaboration between computer scientists and art experts, who guide the research in a useful direction. Everyone I speak to emphasises that humans are working closely with AI, not leaving it to its own devices. "The algorithms are not in and of themselves answering a question. They're feeding into a process," says Higgitt.

Some scholars have disputed whether the Goya portrait has been correctly attributed to the artist. "Understanding the lower portrait may help to more securely say whether it's by Goya or from the right period, even if we can't absolutely say which hand is involved," says Higgitt. For example, an art historian might hope to determine what the man beneath is wearing and what materials were used. So far, a much clearer sense of the man's face has been separated from the neck and headdress of the woman, revealing a serious expression beneath a set of dark eyebrows.

"Conservation has always applied the available technology to the treatment of pictures," says Larry Keith, Head of Conservation at the National Gallery. "It's not such a huge shift to look at technical advances now. It's part of the continuum going back at least 150 years."

'Unwrapping' ancient scrolls

The hope is to produce a tool that will be applicable to other research problems across the heritage sector. Another promising development has been the scanning and "virtual unwrapping" of ancient scrolls that are far too delicate to be opened invasively. In this case CAT scans, generally used in medical contexts, combine X-ray images taken at different angles and can provide cross-sectional images of a scroll. A team at the University of Kentucky in the US are working on papyri scrolls found at Herculaneum and carbonised by Vesuvius.

Sections of papyrus from the scans have been isolated in segments, which are then flattened and merged together, a process that is currently being done manually. Hopes that the metallic elements in the ink would show up in scans were frustrated, as the scroll's writers appear to have used carbon ink. Instead, the team made proxy rolled-up manuscripts using this ink and taught an algorithm to predict where it lies on the scans. The technique is still being perfected, but the team are in the initial stages of applying this to the virtually unwrapped Herculaneum scrolls, left unread since antiquity.

Emmanuel Brun and Vito Mocella

Emmanuel Brun and Vito MocellaIn the 19th Century, a few scrolls were prised open by machines, offering a hint of what lay in wait. These were found to contain ancient Greek and Latin texts relating to Epicurean philosophy, predominantly by the poet Philodemus. Papyrologist and computer scientist James Brusuelas suggests that they may be the earliest surviving copies. Many classical texts are known to us today from medieval versions, but, according to Brusuelas, "when doing things by hand, people make mistakes and Romans didn't necessarily think it was a terrible idea to make changes". If we can read the scrolls, we might get one step closer to what the great philosophers actually wrote. "I think the odds are fairly high that we could get something new, possibly even something we've never heard of before," he adds.

While some of these research efforts are able to tell us what still exists but is hidden, others hope to infer what has been lost. In 2021, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam invited the public to see an AI reconstruction of the lost panels from Rembrandt's The Night Watch. Before it was sliced up, the complete work was, luckily, copied by another artist Gerrit Lundens. The details that were lost are thankfully small, but in the complete version the captain, dressed in black and giving commands to the surrounding civic guardsmen, isn't standing at the centre but instead is further to the right.

The reconstruction was complicated by the many differences between the two works. "There are changes in the palette and style, and Lundens' copy is less than 20% of full scale", says the Rijksmuseum's senior scientist Rob Erdmann, who also notes that the copy is on panel whereas Rembrandt's is on canvas. His mission has been to reverse these effects by teaching the algorithm to convert Lundens' style into Rembrandt's. "For example, the chiaroscuro lighting that he's well known for or the notion that his faces glow," he says.

"The network even mimics the craquelure [tiny cracks] in the paint so I would say it's as scientific as it can be. Which is not to say it's perfect; technology will always improve." Erdmann adds, "this is not like teaching a computer to write in the style of Shakespeare. That involves inventiveness and creativity and knowing what it's like to be human. This is more like a translation engine."

On loan from Amsterdam

On loan from AmsterdamNonetheless, there has been pushback on projects like these as some have questioned what claims to accuracy are being made or whether they have any value. One initiative by Google Arts & Culture to recolour Klimt's Faculty Paintings, which were destroyed in a fire and are known only through black-and-white photographs, is thought by some critics to exhibit excessive artistic licence and reduce the works to "cartoons".

Working already to correct for Lundens' own artistic flair, Erdmann has aimed to limit human aesthetic input, and though the final reconstructed image was approved by expert curators, it was chosen by the algorithm, not hand-picked by the experts from an array of options. "What we were trying to do here is not say that this is definitively what the missing pieces would have looked like," Erdmann says. "Rather, when the pieces were cut off it altered the composition in a meaningful way and we want the public to be able to temporarily suspend disbelief, in the same way as a good novel or movie asks you to suspend disbelief."

"Facsimile helps people engage with the content or original appearance of works of art," says Keith. He recalls visiting exhibitions decades ago that used projectors to similar ends. An even earlier example from the National Gallery is Francesco Pesellino's Pistoia Santa Trinità altarpiece, which was taken apart in 1793. When it was reassembled after being gradually acquired by the gallery, a missing section was repainted in order to complete the composition.

"Now we have the ability to more convincingly reproduce missing constituents, it provides more curatorial opportunities to think about interpretation," says Keith. "The question about how to present a picture remains unchanged, there's just new technology brought to bear on it."

Projects like these, which are upfront about their methods and clear about where the known work ends and the human or computer's interpretation begins, offer the opportunity for us to explore how a lost masterpiece might once have looked. These efforts are part of a long tradition of historical reconstructions, but in recent years they have been created and often experienced digitally, avoiding any need to alter the surviving work. The best attempts are openly inconclusive, acting primarily as a starting point for our own imaginations to fill in the blanks.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.