‘A disposable population’: Pregnant maids face choice between abortion, losing job in Singapore

Once found pregnant, migrant domestic workers will have their work passes terminated. Employers are also expected to report their helpers’ pregnancy. The series Undercover Asia explores the consequences when workers are backed into a corner.

For many, pregnancy is a joyous revelation, but for a migrant domestic worker in Singapore, it could be the start of a nightmare.

*Names have been changed

SINGAPORE: When Vinny* discovered she was pregnant, her husband hoped it was a girl. She hoped it was not true.

Her first thought was, “should I take pills to take it out?”

As a migrant domestic worker in Singapore, being pregnant violated the conditions of her work permit, which would mean deportation and possibly a ban on working here again.

That would spell the end of a financial lifeline for her family of farmers.

“If the crops aren’t good, then we’d (have) nothing to eat, (no money) to buy things. If you don’t have work, how (do) you raise a baby?” said Vinny, who has two sons with her husband.

It did not matter that she had conceived the baby when she was home on leave in the Philippines.

Work permit holders are not allowed to get pregnant or give birth in Singapore unless they are already married to a Singaporean citizen or permanent resident with the Ministry of Manpower’s (MOM)’s approval. This applies even after their work permits have expired or been cancelled or revoked.

According to the MOM, between 2019 and 2021, an average of 170 migrant domestic workers are detected to be pregnant each year.

But the actual number could be higher — the programme Undercover Asia finds out how some workers go out of their way to hide or terminate their pregnancies.

DESPERATE TIMES, DESPERATE MEASURES

The rules in Singapore are so strict that employers are expected to report their helper’s pregnancy to the authorities.

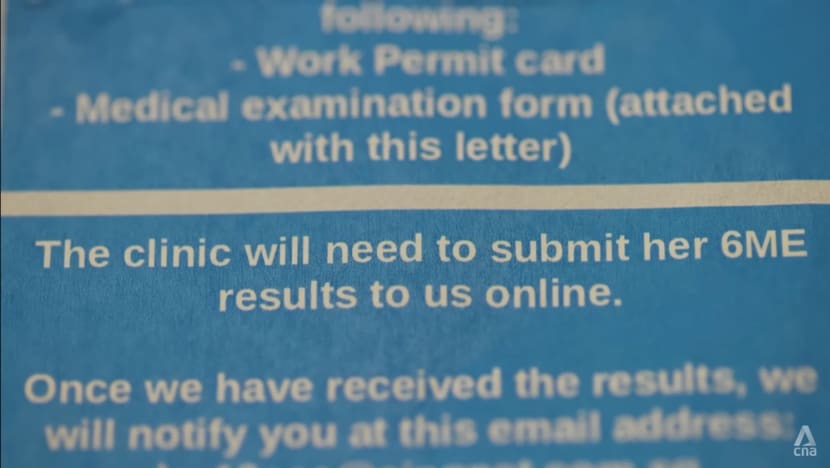

Even if employers keep it quiet, migrant domestic workers must go for health screenings every half a year to be tested for pregnancy, and the results are submitted to the MOM.

It serves as a “regulatory measure” to remind domestic workers that “if you get pregnant, you’ll be detected within six months before the pregnancy fully (goes) to term”, said sociologist Laavanya Kathiravelu.

Vinny was conscious of the clock ticking — her vomiting, headaches and fatigue would give her away in no time. In the second month of her pregnancy, she came clean with her employer, who sent her home without reporting her pregnancy.

“She helped me so that whenever I want to come back, I can easily come back,” said Vinny, who delivered her baby girl a few years ago and has returned to Singapore.

But few are as “blessed” as her. Some domestic workers are desperate enough to risk underground procedures to evade detection.

Just 40 minutes away by ferry, on the island of Batam, a local taxi driver told Undercover Asia about migrant workers from Singapore arriving for illegal abortions.

WATCH: When maids fall pregnant: Labour pains of foreign domestic workers in Singapore (46:29)

By Indonesian law, abortion is allowed only in rare circumstances, such as medical emergencies and cases of severe foetal anomaly. But he said abortion is “widespread” in Batam.

The word on the street is the extracted foetus is shredded in a blender to cover up traces of the procedure, he added.

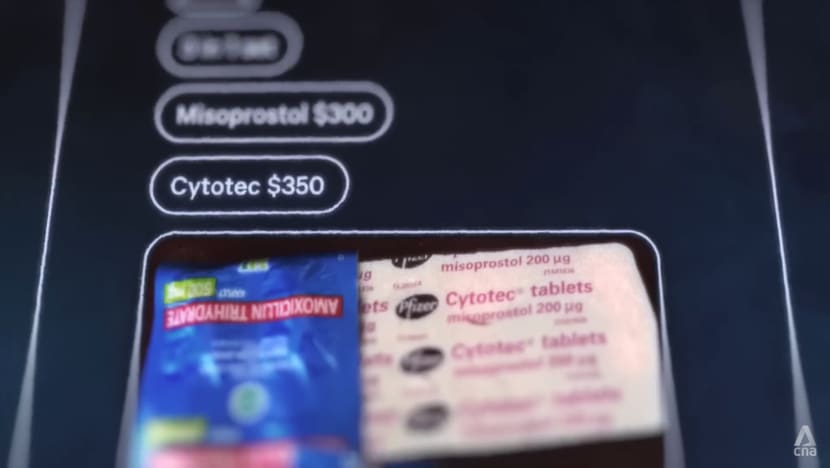

For migrant workers who do not want to take such a risk or cannot leave Singapore, there is a black market for abortion pills on online platforms. But misinformation about the drugs, which a doctor must prescribe, is rife.

When Undercover Asia was chatting with a seller on WhatsApp, posing as a maid who was three months pregnant, the seller offered a drug and said it was safe to end a pregnancy that was past 10 weeks.

“3-5 months is big already. You faster drink (the medicine). Can’t wait,” read the text messages. “Many people do this. You take the medicine. After that, (the foetus will) come out; the blood is just like menses.”

The drug, Misoprostol, otherwise known by its brand name, Cytotec, is typically prescribed to end pregnancies that are less than two and a half months. Beyond that, the chances of a failed abortion are higher.

Taking the drug alone is not always effective either, according to obstetrician and gynaecologist Kenneth Wong, who helms The OBGYN Centre. Another drug, Mifepristone, should be taken first, he said, and “it’s almost impossible to get on the black market”.

If Cytotec alone “doesn’t work completely”, the workers may have symptoms of infection, he said. They would then need a procedure to “clear off the remaining stuff before a severe infection comes in (and) affects their fertility”.

The irony is that abortion is legal in Singapore, and it extends to migrant workers. Doctors are also bound by “sacrosanct” patient confidentiality and “aren’t required by law" to report any abortion to the MOM, Wong said.

But the cost of the procedure — ranging from about S$750 to thousands of dollars in total, depending on any complications and the type of hospital — is something helpers can hardly afford when they earn about S$620 a month on average.

Contraceptives are readily available, but the cost could still be a factor. Condoms can be bought for little over S$4 (three per pack), while birth-control pills and emergency contraception are more expensive because they require a doctor's prescription.

TWO CITIES, TWO DIFFERENT APPROACHES

The pregnancy restriction on migrant workers, which was introduced in 1986, has to do with Singapore’s “citizenship regime”, said Laavanya, an associate professor at Nanyang Technological University’s School of Social Sciences.

The country wants highly skilled immigrants — those on employment passes and S passes, she cited. These workers are allowed to settle here, bring their families along and eventually apply for permanent residency and citizenship.

But those on work permits, like migrant domestic workers, “aren’t seen as having those skills that we desire”, she said. “They’re seen as a disposable population.”

Pregnancy “might create a situation where children of migrants or migrants themselves aspire to a more permanent status”, especially if the child’s father is Singaporean or a permanent resident.

If the mother is not highly skilled and must “draw on state resources”, it would be seen as “a drain on the state”, added Laavanya.

The pregnancy ban is “discriminatory”, said Jaya Anil Kumar, a senior research and advocacy manager in the non-governmental Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics.

It’s in the same spirit as policing what (the workers) do while they’re here on a work permit. … It generally discourages them from cultivating personal relationships.”

Other classes of workers are not subject to these rules, and “it’s a right for every woman to be pregnant if she so wishes”, she added.

In contrast to Singapore, it is illegal in Hong Kong to dismiss migrant domestic workers who are pregnant. Employers will be fined up to HK$100,000 (S$16,900).

And as with every female employee in Hong Kong, if a domestic worker has been employed for at least 40 weeks, employers must provide 14 weeks of paid maternity leave.

Should the worker decide to give birth in Hong Kong, her employer is legally obliged to house her but not her baby.

Employers like Danny*, however, have found the regulations to be burdensome. Three years ago, his helper told him she was pregnant. “I hired her to manage the house and take care of my meals and other needs,” he said.

“So, if she’s unable to do it, and there might even be a possibility that I have to take care of her instead, I feel it’s a bit unfair.”

While his helper was on maternity leave, he had to pay four fifths of her salary as well as hire a part-time helper as a replacement.

In Singapore, employers are unwilling to put up the costs involved, said Laavanya. Employment agencies are also unwilling to do so “because they’re running a profit-driven model”, she added.

“So, unless compelled, I think, by the state … it’s going to be very hard to make this shift in Singapore — or unless the state decides to take on some of that responsibility or financial burden.”

Maid agent Samantha Chan makes a point of drilling this message into every new domestic worker who comes through her doors: “Your purpose here is to earn money. Don’t have a boyfriend, okay? … You’ll get yourself into trouble. You’ll go home.”

‘PEOPLE FALL IN LOVE’

In one employer’s view, the men involved should be penalised just as a pregnancy penalises the domestic worker and the employer.

“(Otherwise), once the maid has been blacklisted, gone home … the cycle starts again (with) a new girl,” said Jewel*, whose helper got pregnant during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The saga cost her S$17,000, which included a S$6,000 abortion and fines for non-payment of salary.

Some of the men are locals, like the “loving” and “very sweet” Chinese Singaporean whom domestic worker Sunny* met.

She fell in love and had a sexual relationship with him. Nine months later, she got pregnant. But when she told her boyfriend to be responsible, he said he had a family.

“(At) that time (in 2015), I felt very stressed and depressed,” said the Indonesian. “I felt like I already (made a) mistake and I needed to (commit) another mistake, which is (to) abort the baby.”

Going home was not an option as she was “scared” that her parents might not accept her for conceiving a child out of wedlock.

Wanting to keep both her baby and the opportunity for employment in Singapore, she lied to her employer about missing her family and wanted to terminate her contract.

Then she stayed in Yayasan Dunia Viva Wanita, a non-profit foundation and shelter in Batam, for about 14 months.

It provides refuge for pregnant domestic workers to see their pregnancy through rather than seek an illegal abortion. Whatever Sunny needed — doctor’s appointments, vitamins, milk powder, food, toiletries — the shelter offered.

She gave birth to a boy and was eventually reconciled with her family, who are now taking care of her child.

Having evaded the blacklist, she has returned to Singapore to work — and to her boyfriend. She hopes that people will not be too quick to point the finger at domestic workers like her.

“The helper also will feel (stressed) themselves. It’s really very stressful,” she said. “(But) people fall in love. You can’t say it’s their fault for falling in love.”

Watch this episode of Undercover Asia here.