Learning in Crisis

Prioritizing education & effective policies

to recover lost learning

Margarita, an energetic 13-year-old student in Imbabura, Ecuador, is hopeful to be back in the classroom after more than a year out of school and in virtual learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even with virtual learning, her family found it difficult to get the tools needed to connect from home. “With the pandemic came the virtual classes but we didn’t have a connection so that I could study.” Margarita is not alone. COVID-19 has caused unprecedented interruptions to schooling.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Learning

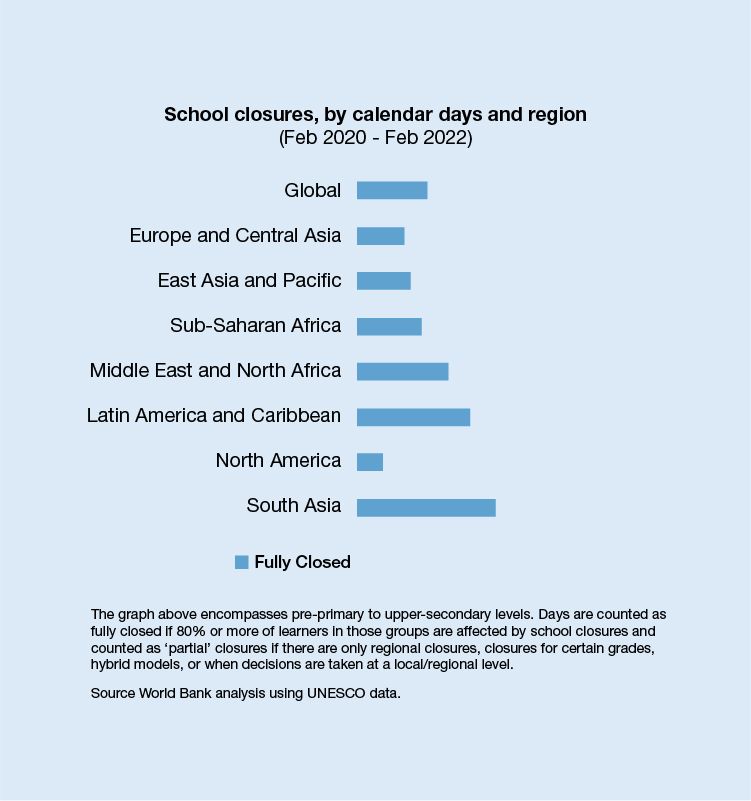

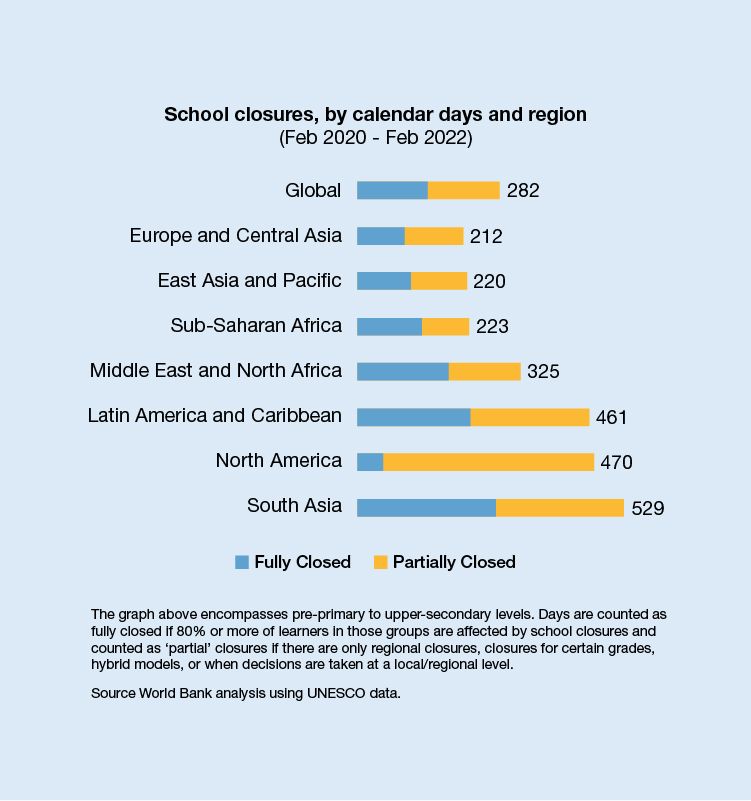

Children around the world have lost an enormous amount of classroom time. At the peak in April 2020, it is estimated that pandemic-related school closures disrupted education for over 1.6 billion children in 188 countries. Globally, from February 2020 until February 2022, education systems were on average fully closed for in-person schooling about 141 instructional days, with the world’s poorest children disproportionately affected.

While some countries quickly reopened schools, many kept all schools fully closed for exceptionally long periods. Others reopened only partially. Many countries that had poor learning outcomes prior to the pandemic also tended to have longer school closures, and prolonged disruptions to schooling exacerbated these inequalities.

We are facing a crisis within a crisis. Learning poverty estimates show that even prior to COVID-19, the learning crisis was already deepening. New data published in “The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update” show that in 2019 learning poverty—the share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10— was at 57 percent, higher than previously thought. After lengthy school closures and unequal access to remote and in-person instruction, learning poverty has increased by a third in low- and middle-income countries, with an estimated 70% of 10-year-olds unable to understand a simple written text.

Additionally, drop-out rates are increasing in some countries, along with early marriage, early pregnancy, child labor, and mental health issues.

Inequality in learning is growing. These school closures have deepened existing disparities in education, with learning losses worst for the most vulnerable children. Across the globe, students from lower socioeconomic status (SES) families were disproportionately affected by COVID-related disruptions to education. Globally, at least 463 million children could not be reached by digital and broadcast remote learning programs amidst school closures, with three out of four unreached students coming from poor households or rural areas.

In Ghana, the learning gap between high-socioeconomic status (SES) and low-SES students widened in both literacy and math.

In Mexico, the share of students who cannot read a simple text increased by 15 percentage points for high SES students and 25 percentage points for low SES students.

Learning Losses Around the World

Source: Where are we on Education Recovery? UNICEF, UNESCO and World Bank. 2022. Based on 65 studies reporting simulated (lighter shades) and actual observed (darker shades) learning losses/gains, covering a total of 104 countries and territories.

In Cambodia, students who failed to demonstrate basic proficiency increased from 34 percent to 45 percent in the Khmer language and from 49 percent to 74 percent in mathematics.

In Rural Karnataka, India, only 16 percent of grade 3 students could perform simple subtraction in 2020, compared to nearly 24 percent in 2018.

In South Africa, grade 2 students incurred learning losses equivalent to up to 70 percent of a year of learning.

School Closures in Latin America

and the Caribbean

Latin America and the Caribbean was hit disproportionately hard in health, economic, and educational terms during the pandemic, and has endured one of the longest spells of school closures. Approximately 170 million students were fully deprived of in-person education for roughly 1 out of 2 school days since the beginning of the pandemic (WBG Brief: My education, our future). Millions of children and teenagers are at risk of dropping out for falling behind academically.

“If we do not act now to recover learning losses, an entire generation of children and young people will be less productive in the future and have fewer opportunities for progress and well-being. This is the time to act, to prevent these losses, to support the future of the next generation.”

Expected and real learning losses are very high, and more severe for earlier grades, younger children, and children from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Average primary education scores in reading and math are expected to fall to levels of more than 10 years ago, in a context where improvements were already very slow. About 4 in 5 sixth graders may not be able to adequately understand and interpret a text of moderate length.

These learning losses are expected to translate into a 12 percent decrease in lifetime earnings for students today. Psychosocial health and well-being have also been greatly affected.

“The first day after the pandemic was declared was like a slap in the face for the educational system.”

The new estimate shows that pre-pandemic learning poverty targets are now out of reach. The Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) committed the international community to eliminate learning poverty by 2030. However, by 2019, it was clear that the world was far off track to achieve this goal. Faced with this evidence, the World Bank also set a supplementary interim target of halving learning poverty. After COVID-19, those ambitious targets appear completely unattainable. The response to this shock to education should be ambition, not acceptance, and we need political commitment, backed up by action, to accelerate learning recovery.

The Learning Recovery: Mitigating the Effects of the Pandemic and Reversing Loses

Future learning and decades of economic and social gains are at stake. Urgent action is needed to ensure this generation of students receives an education that is at least as good as that of past and future generations.

Future learning trajectories are in jeopardy. Learning losses may continue to accumulate once children are back in school. Children risk learning less every year compared to pre-pandemic cohorts.

Learning losses may consist of forgone learning, i.e., learning that did not take place due to school closures, the forgetting of previously acquired learning, and could also include lost future learning.

A cohesive Learning Recovery Program can lead to an accelerated learning recovery.

Source: UNICEF, UNESCO, World Bank. 2021. The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery.

The good news is that we know how to recover learning lost due to the pandemic. A contextually adapted learning recovery program, consisting of evidence-based strategies, can help get students back on their pre-pandemic learning trajectories.

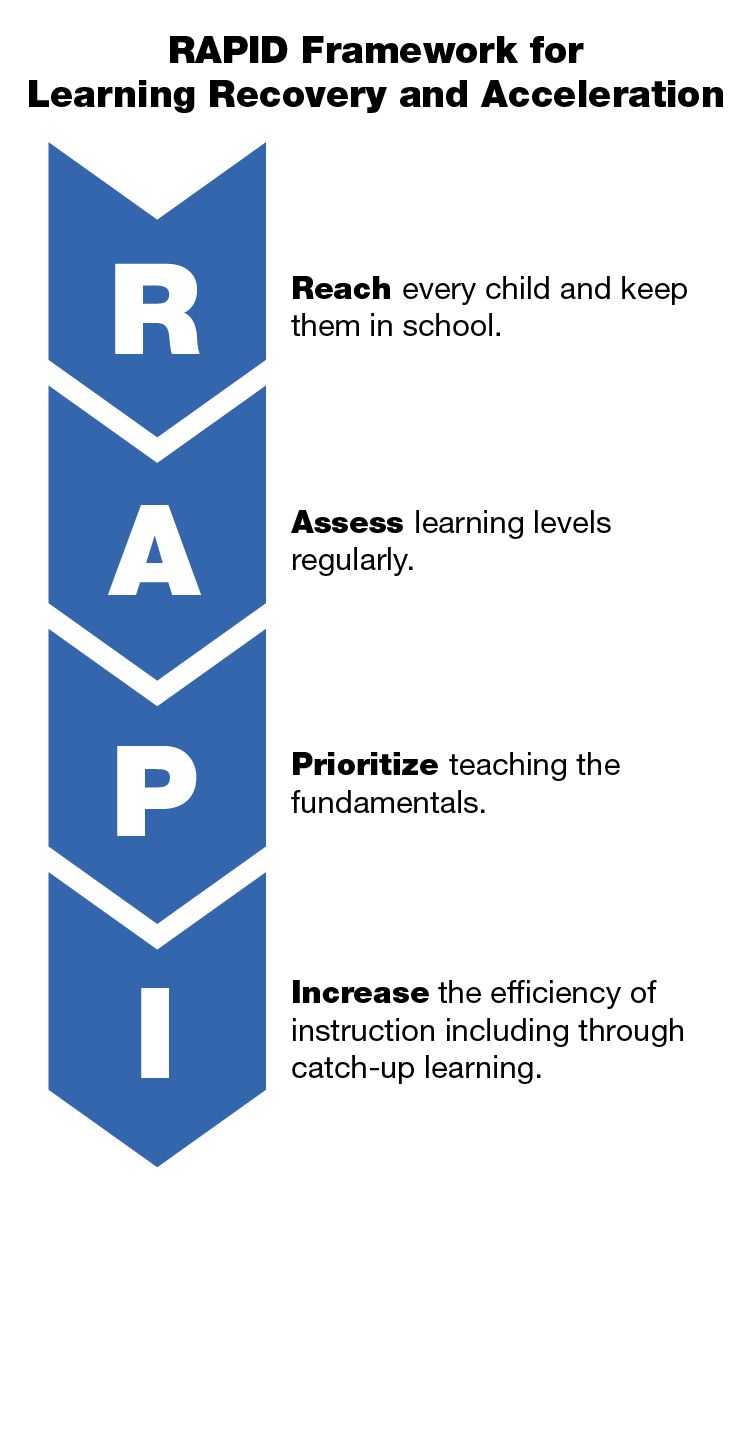

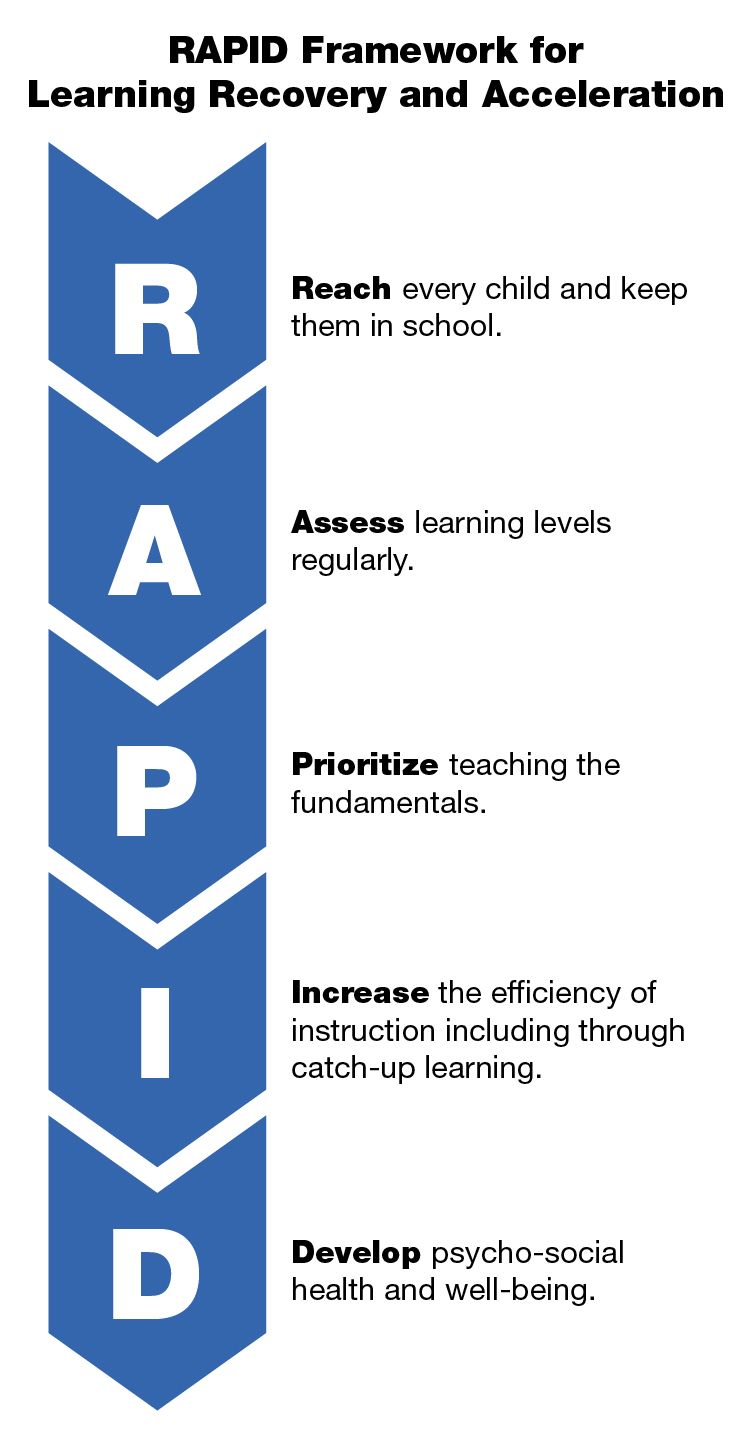

The new RAPID Framework for Learning Recovery and Acceleration introduces five policy actions to establish such a program. While the first two policy actions (i.e., reaching and keeping students in school, and assessing learning levels regularly) support an equitable recovery, including monitoring and planning, the remaining three policy actions constitute strategies to improve teaching, learning, and wellbeing. The composition of the program should be thought of as flexible—a menu of policy options—for countries to select, combine, and adapt to their context.

The central challenge of learning recovery is that objectives must be achieved in less time than for pre-pandemic cohorts. Doing so requires an accelerated framework that urgently brings children back to school, assesses learning levels, and supports more effective teaching and learning. The RAPID framework helps countries:

Education: Accelerating the Learning Recovery with RAPID Policy Actions

Reach every child and keep them in school. The most immediate policy action is to keep schools open and get children back in school. As schools reopen, it is crucial to monitor children’s enrollment and understand why some children have not returned to school.

Assess learning levels regularly. Baseline measures of learning help make informed decisions on where and how to mobilize resources at a system level to prevent learning loss and drop-out among those most vulnerable. Better data and indicators will be crucial. Existing efforts to collect and use data tend to be fragmented and infrequent, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where the effects of the learning crisis are most severely felt.

Prioritize teaching the fundamentals. Given the staggering loss in instruction time, learning recovery efforts should focus on essential missed content and prioritizing the most fundamental skills and knowledge needed to move ahead. This will require adjustments to teaching methods, such as targeting instruction in order to meet students’ learning levels, as well as ensuring curriculum are focused on the core skills and knowledge children will need at their respective grades.

Increase the efficiency of instruction including through catch-up learning. To catch-up on lost learning, school systems will need to support initiatives that increase the amount of learning within classrooms, including better trained teachers and employing learner-focused recovery strategies (i.e., individualized self-learning programs, tutoring and coaching, accelerated learning programs, and catch-up programs for dropouts).

Technology and innovation also play a role in achieving these goals. Remote and hybrid education is here to stay. By providing teachers with access to technology and the skills to use technology effectively to enhance education delivery can help prepare education systems for future shocks and help teachers remediate gaps in learning.

Develop psycho-social health and well-being. The pandemic has compounded risks for children and youth who are already vulnerable, including women and girls, children with disabilities, and children who are living in protracted settings of conflict or displacement. Addressing the mental health and psychosocial needs of children and youth and supporting their wellbeing is important in and of itself but is also critical to ensuring that they can learn.

In March 2022, a joint UNICEF, UNESCO and World Bank report provided an update on what countries are doing in terms of policies and initiatives for education recovery. Around 90 countries responded that they are implementing specific programs to mitigate learning losses.

Pre-pandemic, the government of Gujarat, India introduced periodic assessment tests (PAT), formative weekly classroom assessments for each subject, linked to timetables and mapped to learning outcomes.

The use of PAT on a digital platform allows for monitoring of student learning outcomes and adapting learning to students’ levels. During the pandemic, PAT results were used to personalize remote education to the level of each student.

In October 2021, Vietnam’s Ministry of Education released curriculum guidelines that encourage schools to adjust teaching plans to their specific needs, in large part by focusing instruction on the most important material.

For each content area, the guidelines define expected learning outcomes and suggest how to consolidate and focus teaching and assessment from the official curriculum. Suggestions for focused teaching include having students read before class; having teachers select among the lessons that cover the same content and skills; and streamlining duplicate content within and between subjects.

There is also guidance on how teachers can work with parents to help children learn, including helping students practice reading and spelling skills at home.

In Kenya, Tusome (“Let’s Read” in Kiswahili) is a flagship partnership between USAID and the Kenyan Ministry of Education to focus on four key interventions: enhancing classroom instruction, improving access to learning materials, expanding instructional support and supervision, and collaborating with key system-level literacy actors.

As a result, students made substantial gains in English (proportion of non-readers fell from 38 to –12 percent) and Kiswahili (proportion of non-readers fell from 43 to 19 percent).

Western and Central Africa’s Strategy to Reduce Learning Poverty

Despite recent progress, education in the region is in crisis. 80 percent of 10-year-old children in Western and Central Africa are unable to read and understand a simple text, and more than 32 million children remain out of school, which represents the largest share of all regions worldwide.

Imagine all girls and boys arrive at school ready to learn, acquire quality education, and enter the job market with the skills to become productive and fulfilled citizens. Leaders from Western and Central Africa endorsed this vision in the Accra Call for Action on Education during a ministerial meeting co-hosted by the Ghana Vice President Dr. Mahamadu Bawumia with more than 40 ministers of finance and education across Western and Central Africa. During the event, the new World Bank regional education strategy "From School to Jobs: A Journey for the Young People of Western and Central Africa" was unveiled, setting ambitious targets to deliver results at scale by 2030. The World Bank will roll out the strategy at country level and move to operationalizing and monitoring Accra commitments, notably to increase financing for the education sector and focus on the targets of the strategy, including reducing learning poverty.

If implemented well and sustained over time, many of the policies outlined can reverse learning losses, strengthen the longer-term fight against learning poverty, and will be levers for systems around the world to build forward better.

Commitment to Reverse the Effects of the Pandemic

Strong political commitment—at both the national and global levels—to prioritize learning of all children is a crucial first step in reversing the learning deficit resulting from the pandemic. Real commitment means clear targets, prioritization of policies and resources, and financing.

Recovery must start with political commitment at the national level. To lead to broad, sustained acceleration of learning, these short-term interventions must be implemented at scale, and this implementation must be part of a national strategy of structural reforms over the longer term. National coalitions for education are needed to support high-level commitment. Recovering the learning losses of children and youth requires the efforts of educators, families, and administrators throughout the system.

Global commitment is also needed. A coalition of organizations is raising awareness of these issues, advocating for ambitious yet realistic targets, providing knowledge and evidence of what works, and providing financial support. These organizations include the World Bank Group, UNESCO, UNICEF, UK government Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The World Bank stands with countries as they work to accelerate learning recovery. As the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, the Bank’s portfolio of over $23 billion aims to improve learning and provide everyone with access to the education they need to succeed. Over the last three years, the Bank’s lending for education has doubled compared to the preceding 10 years. Projects are reaching at least 432 million students and 18 million teachers—one-third of students and nearly a quarter of teachers in client countries.

Countries around the world are invited to endorse the Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning which recognizes that foundational learning provides the essential building blocks for all other learning, knowledge, and higher-order skills. In doing so, they will join members of the global education community and other partners, including civil society and youth organizations as they commit to taking urgent and decisive action to reduce by half the global share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age ten, by 2030.

With the urgent implementation of these policies, it is possible to recover and accelerate learning and to build more effective, equitable, and resilient education systems. This is what is needed to increase learning by as much as possible by 2030—and continue that work beyond 2030—and to ensure that all children and youth have the opportunity to shape the future they deserve.

The data used to calculate learning poverty has been made possible thanks to the work of the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning led by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), which established Minimum Proficiency Levels that enable countries to benchmark learning across different cross-national and national assessments. Economists at the World Bank use simulations to gauge the likely magnitude of the increase in learning poverty. These simulations take into consideration a few key variables, including the duration of school closures, pre-COVID rates of learning, and the likely efficacy of remote learning during the period when schools were closed.