How Putin’s global network aids and abets his ambitions

The economic and political backing of China, the military support of Iran and North Korea, and the strategic depth granted by Belarus are some of the cornerstones of the Kremlin’s powers of endurance

In its attack on Ukraine and its challenge to the world order Putin's Russia has the indispensable backing of several international partners

China provides Moscow with economic fuel including increased supplies of key products while also importing Russian natural resources

Iran provides vital military support by delivering drones and missiles

North Korea facilitates Putin’s war effort by supplying artillery ammunition

Belarus provides Moscow with strategic depth by accommodating part of its nuclear arsenal

Caucasian and Central Asian countries are important markets for the Kremlin’s efforts to sidestep Western sanctions

In his war against Ukraine and his brutal challenge to the world order, Vladimir Putin has a vast network of international support. The countries within his web engage in varying levels of complicity, from explicit political backing for the invasion of Ukraine from states such as North Korea, Belarus, and Syria, to an implicit desire for the invasion to succeed or a mere willingness to take advantage of the situation in a way that just happens to benefit the Kremlin. All together, this network has pumped indispensable economic and military oxygen into Moscow’s ambitions.

China provides essential commercial support, with a notable increase in both the sale of products to Russia and the purchase of Russian fossil fuels, thereby helping the Kremlin to survive Western sanctions. Iran and North Korea deliver key weapons to sustain the offensive in Ukraine. Belarus affords the Kremlin strategic depth by allowing it to use its territory for multiple purposes.

This core network of cooperation has a political relevance that places it on a prominent plane with respect to other dynamics that favor Putin. Time will tell whether these countries converging in a pulse against the West, yet without a formal alliance, will come to form a highly cohesive partnership. For the time being, they offer Russia significant help.

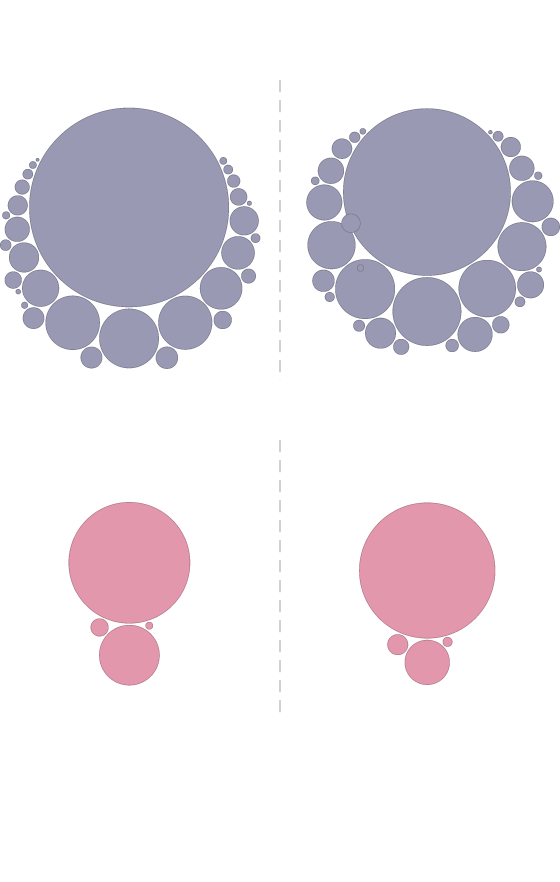

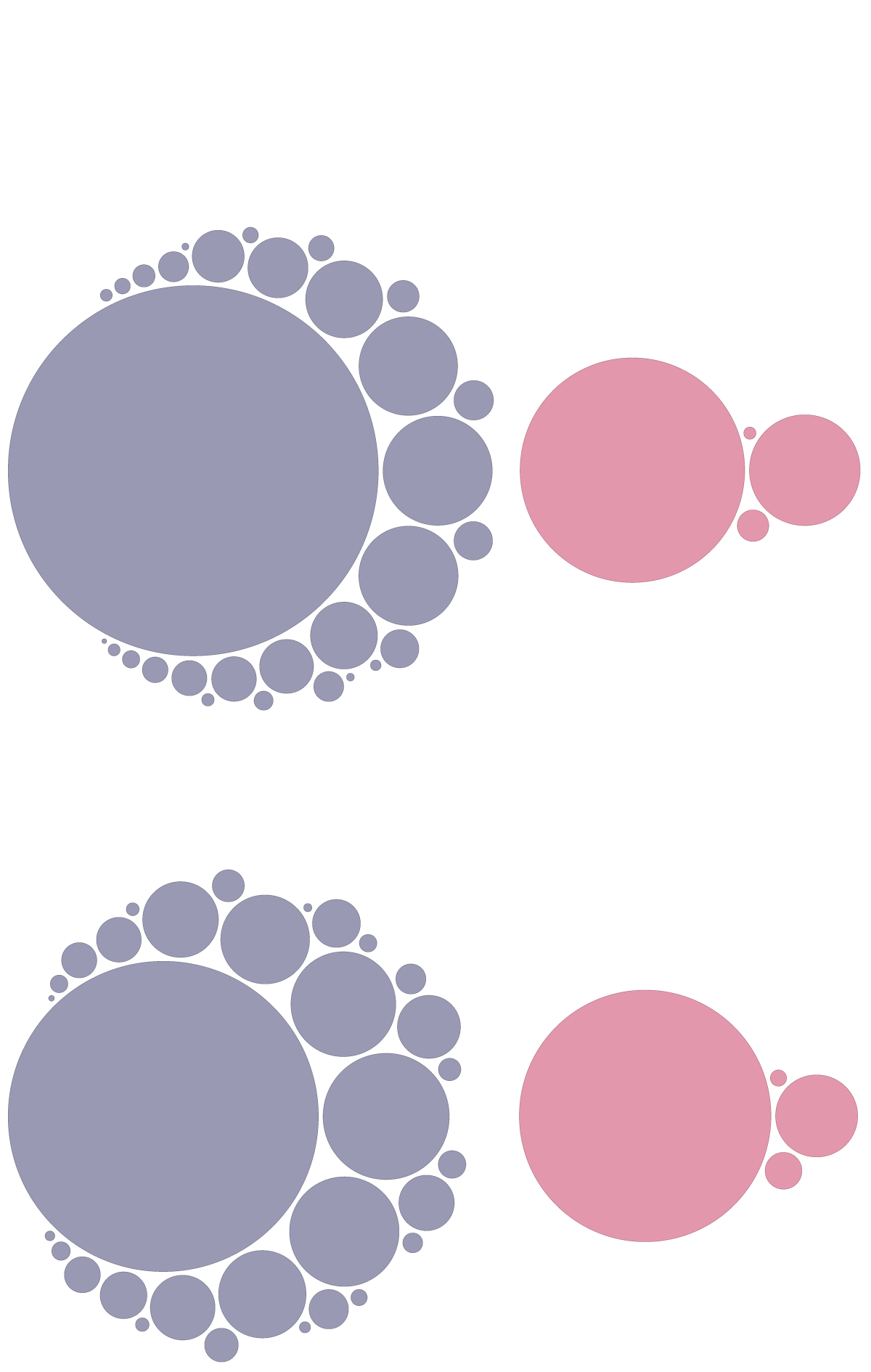

Defense expenditure

Gross domestic

product

EE UU

EE UU

811

(billion )

26 T

Turkey

Spain

Canada

Italy

Spain

France

Italy

U.K.

Canada

Germany

France

Germany

U.K.

NATO countries

China

China

297 B

17.7 T

Iran

Bielorr.

Iran

5 B

Bielorr.

0.7 B

366 B

68 B

Russia

Russia

71 B

1.9 T

Russian partners

Data in billions and trillions of dollars

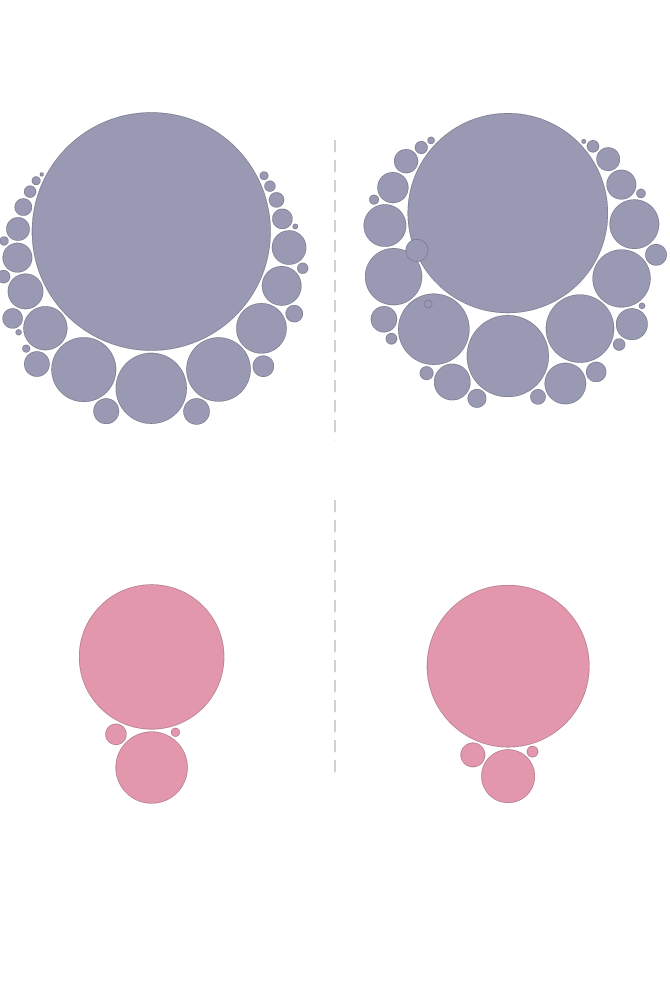

Defense expenditure

Gross domestic

product

EE UU

EE UU

811

(billion )

26 T

Turkey

Spain

Canada

Italy

Spain

France

Canada

Italy

U.K.

Germany

France

Germany

U.K.

NATO countries

China

China

297 B

17.7 T

Iran

Belarus

Iran

5 B

Belarus

0.7 B

366 B

68 B

Russia

Russia

71 B

1.9 T

Russian partners

Data in billions and trillions of dollars

Defense expenditure

Data in billions and trillions of dollars

NATO countries

Russian partners

Portugal

Spain

21 B

Italy

34 B

France

Belarus

56 B

Norway

0.7 B

Russia

China

United States

U.K.

71 B

297 B

811

(billion)

69 B

Sweden

Iran

Germany

5 B

57 B

Canada

Poland

Greece

Turkey

Gross domestic product

Spain

Italy

1.6 T

2.2 T

Greece

France

The

Netherlands

3 T

Belarus

68 B

China

Russia

United States

Germany

17.7 T

1.9 T

26 T

4.4 T

Poland

Iran

U.K.

366 B

3.3 T

Canada

Sweden

Turkey

2.1 T

On another level, there is the role of countries which, lacking any political intention comparable to those above and with varying degrees of empathy, or a simple disinterest in Russian abuses, shore up the Kremlin via trade, minimizing the impact of Western sanctions. “The West’s sanctions policy has failed to deter Russia and is currently struggling to succeed in containing it. The main loopholes are centered around oil and battlefield goods. The successful circumvention of the oil price cap and the re-export of critical items allow Russia to defy restrictions. In both cases the role of third countries is pivotal”, says Maria Shagina, from the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Beyond the fundamental role of China, several Central Asian and Caucasian countries are emerging as useful black markets for the Kremlin, though many other nations play important roles. Shagina sums up the map as follows: “China, India and Turkey buy 90% of Russian crude oil. China and Hong Kong are the key hubs for sourcing dual-use goods like semiconductors. The UAE has become a critical node in Russia’s circumvention strategy - either as a transshipment hub or a financial hub”.

There is also a third tier, which has political significance. Countries such as Syria and Eritrea support the Kremlin’s cause; there are others that are very empathetic, such as Venezuela, several African states that receive security aid from Moscow, and Hungary, which has tried to obstruct EU policy regarding the successive rounds of sanctions, though with little success. There are also politicians and political parties that, within many Western societies, express an empathy towards Putin and his approach. An obvious case is that of Donald Trump who, without even having yet won this year’s presidential elections, has already succeeded in getting the Republicans to stall U.S. aid to Ukraine for the past seven months. It remains to be seen what he will do if he returns to the White House.

It is a broad, complex and nuanced picture. Here is a look at some of its key features.

China

Beijing has refused to provide military support to Moscow, but significant growth in bilateral trade is what is mainly fuelling Russia’s economy and its ability to sustain the war effort in Ukraine. In 2023, there was trade worth $240 billion, up 26% from the previous year, a figure that equals EU-Russia trade in 2021 prior to the invasion.

As well as microchips — perhaps the most essential item — smartphones, computers, industrial and construction machinery and automobiles are some of the main Chinese products that have allowed the Russian economy to continue to function with some normality despite Western sanctions. Conversely, China has bought large quantities of oil, and also coal, copper, and nickel, guaranteeing important sources of revenue for the Kremlin. Half of Russian oil exports went to China in 2023, according to Russia’s deputy prime minister, Alexander Novak.

Beijing is cultivating the most strategic of all its international relations with Moscow. In the current context, China has a clear interest in avoiding a Ukrainian victory that would strengthen the West and increase the risk of Putin’s downfall. Beijing does not want a collapse of the Russian regime, which might open up an opportunity, however small, for the democratization of Russia, as this would entail the risk of a Kremlin on better terms with the West and a scenario that Beijing considers a nightmare — one in which it would be surrounded by unfriendly nations, including India, South Korea, Japan, etc.

“What we are seeing is basically a realignment of Russia which, after the break with Europe, embraces the call from Eurasia,” says Jorge Heine, professor at the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and former Chilean ambassador to China and India. “It is boosting relations with China, and also with India and Iran; for example it has come up with a project to relaunch a railway connection from St. Petersburg to Iran.”

According to Heine, author of Xi-na in the Century of the Dragon, “although publicly there is talk of a relationship without limits, that is rhetorical. Of course, there are limits. China doesn’t trade arms and drives a hard bargain on Russian gas. There is some rivalry between the two over the Central Asian space. The relationship is not based on charity, but on interests. But both show signs of wanting to manage the rivalry, because it is in their interest to agree and face what they understand as the challenge from the West and NATO together.”

The two countries have announced plans to redouble Russia’s piped gas supply capacity to China. Implementation, however, is slow, and experts agree that China is exerting the full weight of its superiority by seeking to obtain extremely advantageous prices.

China’s limited support is also evident on a purely political level. Beijing has never criticized and thereby weakened Moscow’s position, but neither has it voiced explicit support for the invasion and has instead issued clear warnings against the use of nuclear weapons when Putin issued the threat. China does not want Russia to lose and therefore supports it, but at the same time fears that excesses by Russia — or North Korea — could end up galvanizing the West’s support for Ukraine and its strategic preparedness.

Beijing provides Russia with indispensable support, so much so that the latter now finds itself in a position of absolute inferiority and dependence on China, which cultivates the relationship within a millimetric calculation of their interests — interests which are not balanced as China’s huge economy extracts a much greater benefit from the stability of the global system. “China and Russia have always had some converging and some diverging interests. But now, unlike in the not too distant past, the former predominate,” Heine says.

Iran

The Iranian regime provides Putin with critical backing militarily by delivering drones that have boosted Russian airstrike capabilities against Ukraine. Reuters recently published information that also points to the supply of hundreds of Iranian ballistic missiles to the Kremlin.

“Although relations between Iran and Russia deepened notably from the support they both gave to [Syrian President Bashar el] Assad, it has paradoxically been the sanctions that the West has imposed upon the two that have brought them much closer together,” explains Luciano Zaccara, a professor at Qatar University specializing in Persian Gulf studies.

“The Iranian political class has always been divided over the level of closeness it wants to have with Moscow, with conservatives more interested in using the Russian card to offset the impossibility of restoring ties with European countries, especially since the arrival of [Ebrahim] Raisi as president.” Zaccara adds.

That there are mutual interests is obvious. Moscow is in dire need of the war materiel that Tehran can supply as a prolific producer of drones and missiles. There is speculation that Iran has even helped in setting up new drone production lines in Russia. Swarms of cheap drones wear down Ukraine’s expensive anti-aircraft defenses.

Iran, in turn, has multiple interests, especially in terms of the supply of advanced technologies in Russian hands. Zaccara notes Iranian interest, for example, in Su-35 fighter jets to upgrade their aging air fleet.

Iran is also interested in a greater commercial overlap. Tehran “has been trying for years to enter the automobile market in Russia with its Iran Khodro and Saipa plants, whose chances have improved as a result of Russian sanctions on European companies,” Zaccara notes. At the end of 2023, Iran sealed a free trade agreement with the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union.

According to Zaccara, “moving between the two emerging powers — Russia and China — seems to be the most pragmatic and effective non-exclusive strategic option a Tehran in need of weighty allies could take.”

North Korea

The North Korean capital of Pyongyang is another important military cornerstone for Putin. The North Korean regime is supplying huge quantities of ammunition, an essential element in a war in which the production of sufficient material is a serious challenge. Ukrainian authorities have reported that Russia has used at least 50 North Korea-produced missiles against its territory.

The rapprochement between the two countries has been framed by a summit between Kim Jong-un and Putin, in which the former promised the latter to “always be together” in the “sacred war” against the West. Like Iran, North Korea has an interest in certain Russian technological capabilities. Although diminished by war, sanctions and brain drain, Russian society obviously has technical-scientific know-how of great interest to other countries in strategic areas. In the case of North Korea, an impoverished country, food exports on favorable terms are also of interest.

Extremely dependent on China, Pyongyang has undoubtedly calculated that it is in its interest to earn credits from Russia, which allows for a useful strategic triangle. The supply of weapons for use in Ukraine, on the other hand, allows for a test of their quality on the battlefield.

Central Asian and Caucasian countries

Several former Central Asian and Caucasian Soviet republics have recorded considerable increases in trade with Russia after EU sanctions were imposed.

“Many ex-Soviet countries used the opportunity to capitalise on Moscow’s isolation and became intermediaries between the West and Russia. Lax regulatory policy and lack of capacity-building made evasion thrive”, observes Shagina of the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Some of these countries are more in tune with Moscow than others. Collectively — and not necessarily with much strategic calculation — they function as black markets that help the Russian economy circumvent restrictions.

Belarus

Belarus is a quasi-vassal state of Russia, and lends Putin’s ambitions significant support, offering strategic depth by merely making its territory available for multiple uses. Part of the February 2022 invasion was launched from Belarus, which today hosts Russian nuclear warheads and whose leader, Aleksandr Lukashenko, acted as a mediator between Putin and the deceased Russian mercenary leader of the Wagner group, Yevgeny Prigozhin, with an agreement to relocate Wagner mercenaries to Belarus.

Other countries

There are, of course, other countries that, in different ways, have aided Putin’s Russia amid its ongoing aggression in Ukraine. India, for example, has sharply increased its purchase of Russian crude, from virtually zero before the February 2022 invasion to two million barrels per day in July 2023, taking advantage of the low cost. This figure has fallen, however, hovering around 1.3 million at the beginning of the year, probably due to improvements in the design of Western restrictions. Also in the energy sector, those who have collaborated in transportation, including Greek shipowners, or in providing storage and refining services, such as Singapore, have been of significant help to Russia.

In political terms, a role is being played by figures such as Marine Le Pen, president of France’s far-right National Rally, who propagates ideas in French society that suit Putin. But it is Donald Trump who is the key player in this scenario. He has already warned that, as far as he is concerned, Russia can “do whatever the hell they want” with NATO countries that do not spend the stipulated 2% on defense. These include Italy and Spain. Putin recently said that he would prefer a second Biden term. But then he also said he had no intention of invading Ukraine.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition