In May 2014, I reported on my efforts to learn what the feds know about me whenever I enter and exit the country. In particular, I wanted my Passenger Name Records (PNR), data created by airlines, hotels, and cruise ships whenever travel is booked.

But instead of providing what I had requested, the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) turned over only basic information about my travel going back to 1994. So I appealed—and without explanation, the government recently turned over the actual PNRs I had requested the first time.

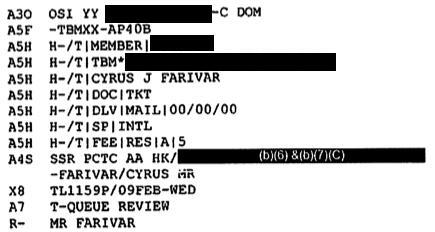

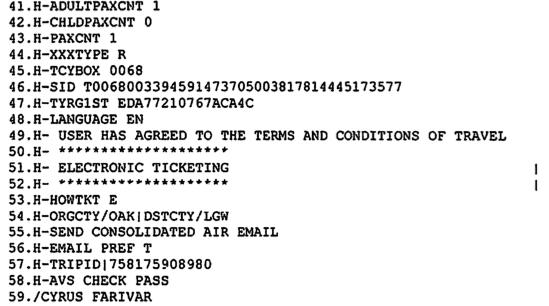

The 76 new pages of data, covering 2005 through 2013, show that CBP retains massive amounts of data on us when we travel internationally. My own PNRs include not just every mailing address, e-mail, and phone number I've ever used; some of them also contain:

- The IP address that I used to buy the ticket

- My credit card number (in full)

- The language I used

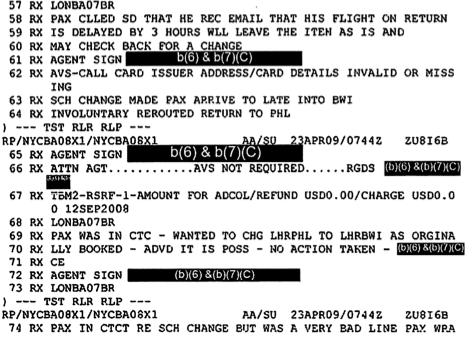

- Notes on my phone calls to airlines, even for something as minor as a seat change

The breadth of long-term data retention illustrates yet another way that the federal government enforces its post-September 11 "collect it all" mentality.

Parsing PNRs

Parts of my PNRs, such as travel itineraries, were easy to understand. Others were nearly impossible to parse, so I enlisted the help of Edward Hasbrouck, a travel writer who has extensively researched (and even filed lawsuits over) PNRs. He told me that PNRs like mine are created for domestic flights, too, but that it's only for international travel that data is routinely given to CBP.

I was most surprised to see my credit card details—full card number and expiration date—published unredacted and in the clear. Fortunately, that credit card number has long expired, but I was nonetheless appalled to see it out there. American Airlines, which had created that particular PNR in 2005, did not immediately respond to my request for comment on how or why such detailed personal information would show up here. (In other instances, the majority of the number was X’d out.)

Loading comments...

Loading comments...